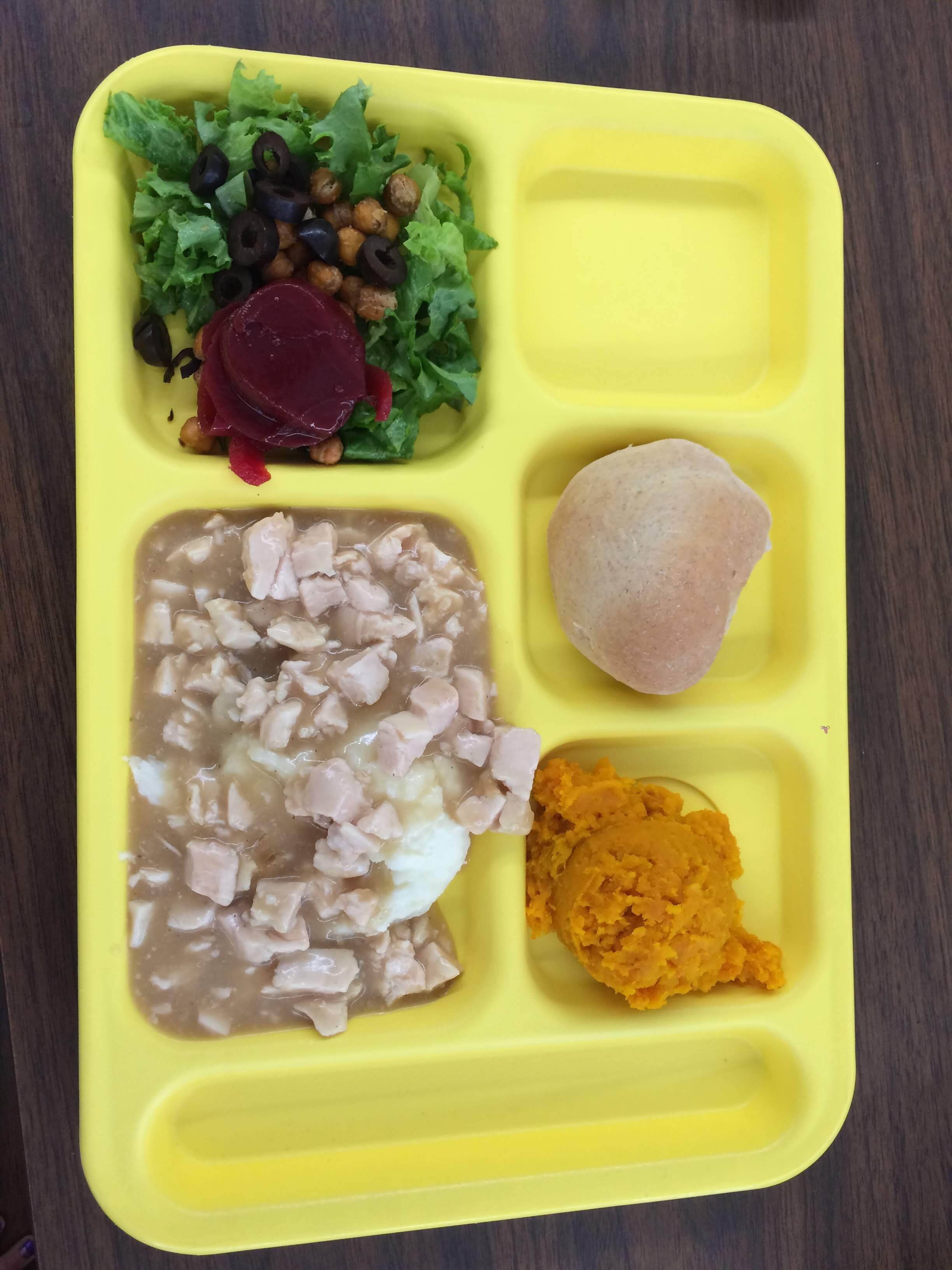

School lunch never tasted as good to me as it did on Tuesday, September 28, when I sampled a delicious Thai meal in the BUHS cafeteria. Thanks to “Where in the World are We Eating,” a new program by Brattleboro Regional Food Service Director Ali West of Fresh Picks Cafe, all Windham Southeast School District (WSESD) students had the opportunity to visit Thailand with their taste buds last month. Rather than the standard lunch fare of mac and cheese, pizza, and sandwiches, students could sample chicken satay, tofu Pad Thai, vegetarian Tom Kha soup (my favorite!), and mango sticky rice.

Ali was inspired to create this program to bring the entire school community together to celebrate the diversity of our school district through the shared experience of food. She collaborated with the district’s ESOL teachers to compile a list of the 22 countries students in WSESD are from. Twenty-two countries is a lot to fit into one school year, so she selected nine countries (one per month) to focus on this year, and she plans to continue the program and visit more countries in the future. Thailand is just the beginning! Here is the complete list of countries that students will get to explore with their taste buds this year:

September - Thailand

October - Jordan

November - Haiti

December - Germany

January - Kenya

February - Syria

March - The Philippines

April - Jamaica

May - Bolivia

Ali is encouraging the entire school community at all nine schools in the district to get involved, with invitations to music, art teachers, and librarians to feature music, art, and literature highlighting these countries with their students throughout the year. Invitations have also gone out to 6th-12th grade social studies teachers to take turns doing an in-depth study with their students on the featured country. As a culmination of this research, students will create slideshows to share with students of all ages throughout the district to teach about each country’s flora, fauna, clothing, and scenery. For Thailand, Sarah Kaltenbaugh’s 6th graders at Academy School created an engaging slideshow that highlighted beautiful statues, floating markets, and clouded leopards. This slideshow was shared with students from pre-K through high school seniors during the special meal. Early grades can decorate their school cafeterias with coloring pages incorporating images from each featured country.

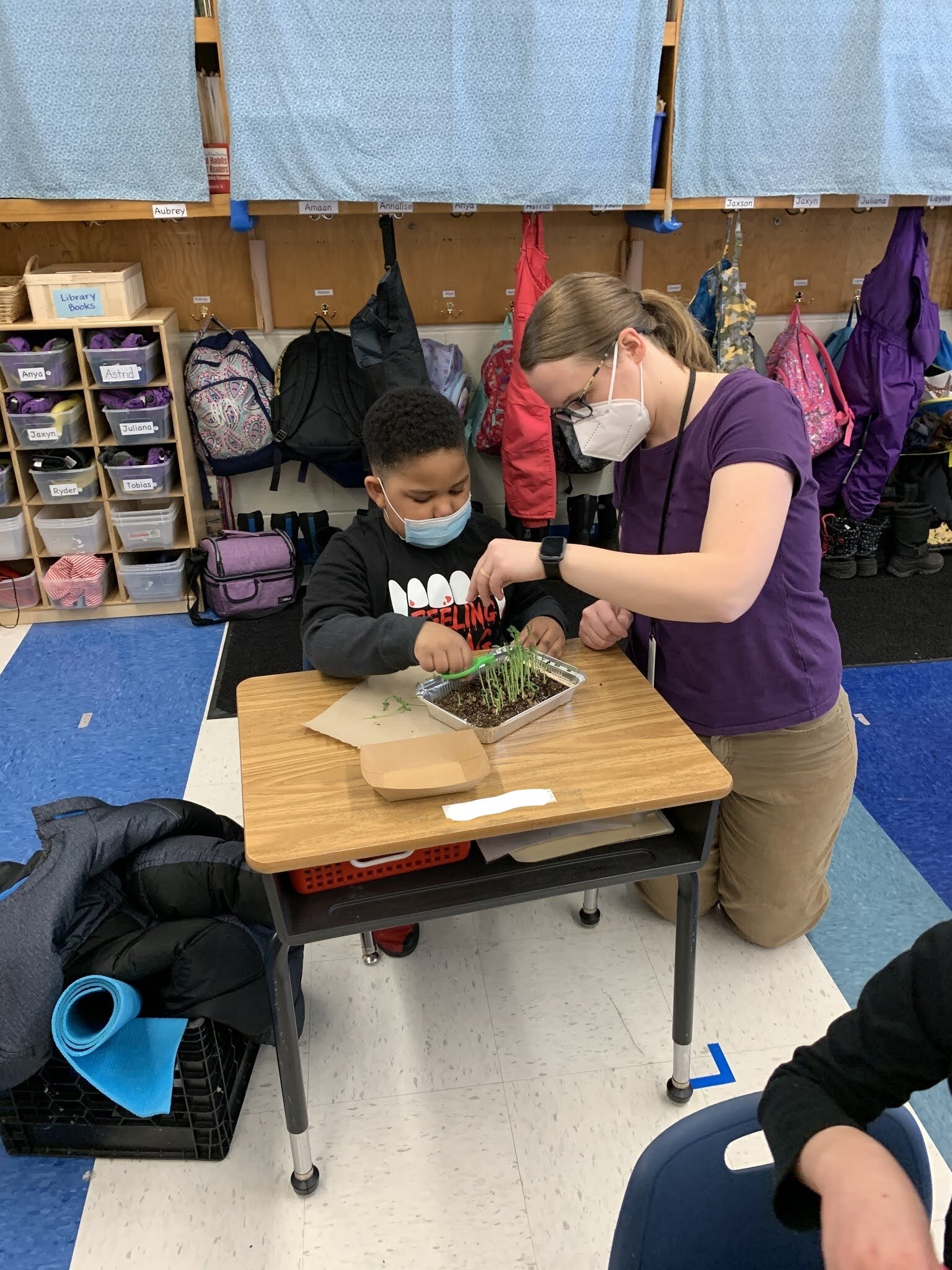

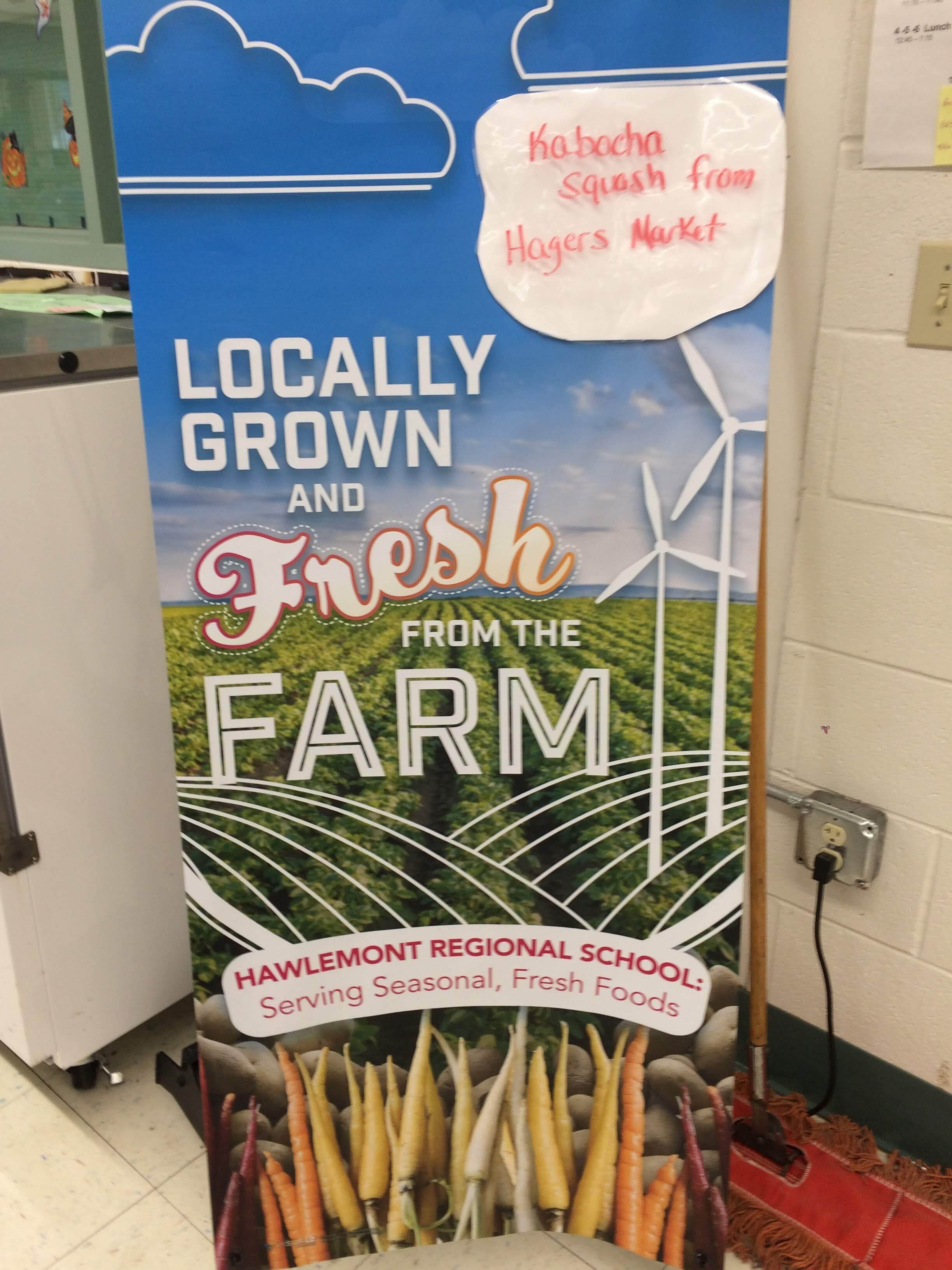

“I want all of our students, no matter where they are from, to feel welcomed and celebrated in our schools,” says Ali West. As a chef and food service director, the best way that she has found to do this is through a celebration of diversity in the school meal program, which is accessible to all students again this year thanks to the USDA extension of universal meals. Ali even met the added challenge of including local produce in the meal by purchasing bean sprouts from the Chang Farm in Whately, MA, through the Food Connects Food Hub.