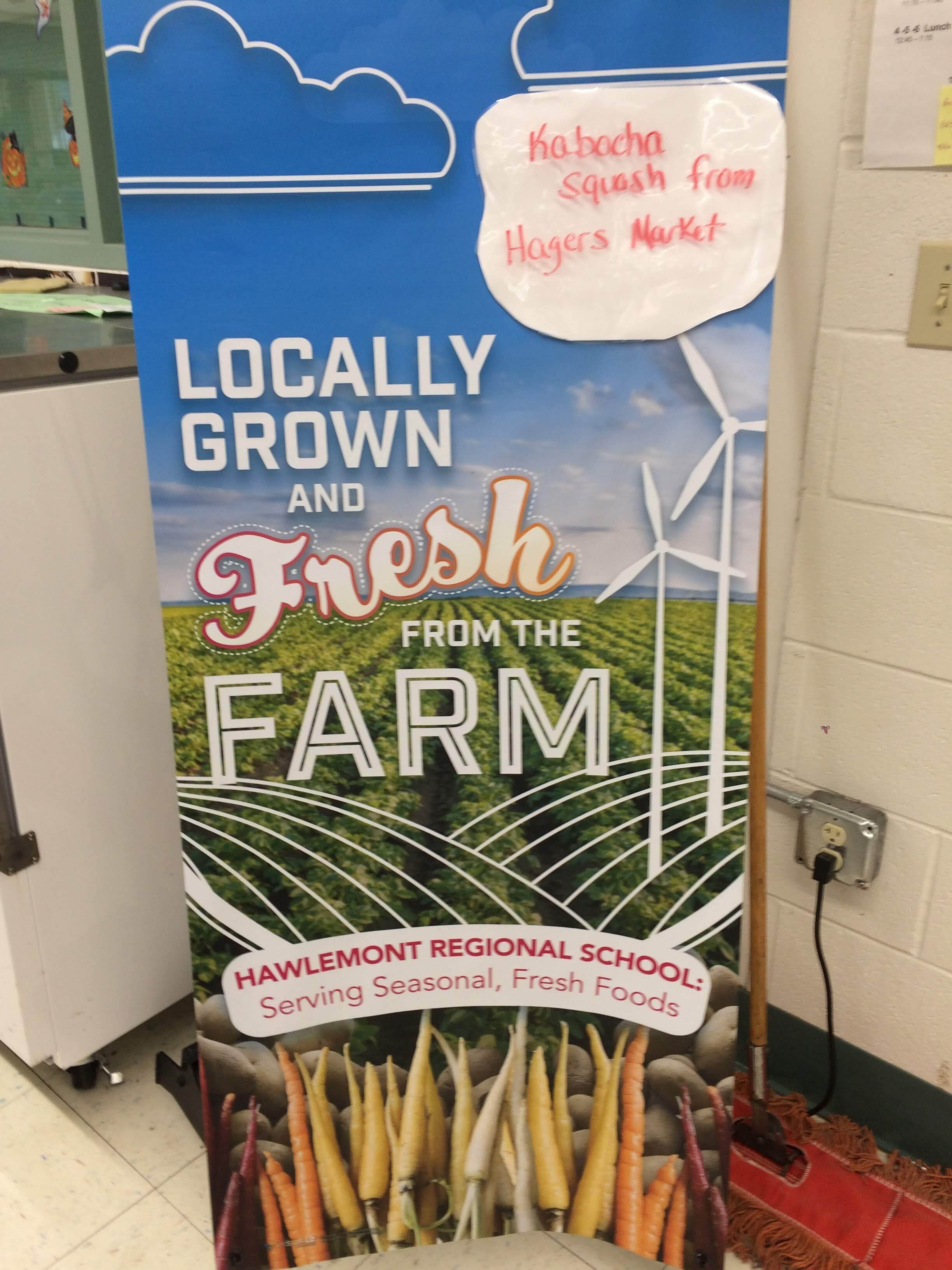

The youngest Oak Grove School community members recently completed a delicious in-depth study of local foods, gardening, and cooking! Oak Grove School’s Pre-K program was one of the 2021 Early Childhood Education CSA grant recipients through the Vermont Agency of Agriculture. In its first year, this grant subsidizes 80% of the cost of a community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm share at the Vermont farm of your choice. Oak Grove’s Pre-K chose to work with Full Plate Farm in Dummerston, VT.

13 lucky 4 to 5-year-old students got to enjoy many locally grown treats this year, including radishes, kale, beets, scallions, brussels sprouts, and winter squash. It was their first time trying some of these new flavors for many students. Pre-K staff Jen Tourville and Jamie Champney and garden coordinator Tara Gordon found creative ways to inspire the students to try new things. Adding mystery to the tasting lessons was one successful approach—from the five senses mystery box to mystery smoothies, student curiosity was encouraged.

Each week, Jen and Tara put a different produce item into the five senses mystery box—an oatmeal container with a sock sleeve attached by a rubber band. They invited the students to put their hand in and feel the item and describe it with words, strengthening their language skills while also piquing their curiosity.

Recently, Jamie made a mystery smoothie for the class with bananas, frozen berries, yogurt, and a mystery ingredient (spinach). “Some students had never been willing to taste a smoothie before because they were already convinced that they wouldn’t like it,” Jamie said. “Adding mystery to the activity made all students curious enough to try it, and big surprise—they all liked it!” After they had tasted the smoothie and made guesses about the secret ingredient, Jamie revealed the spinach to her surprised students.

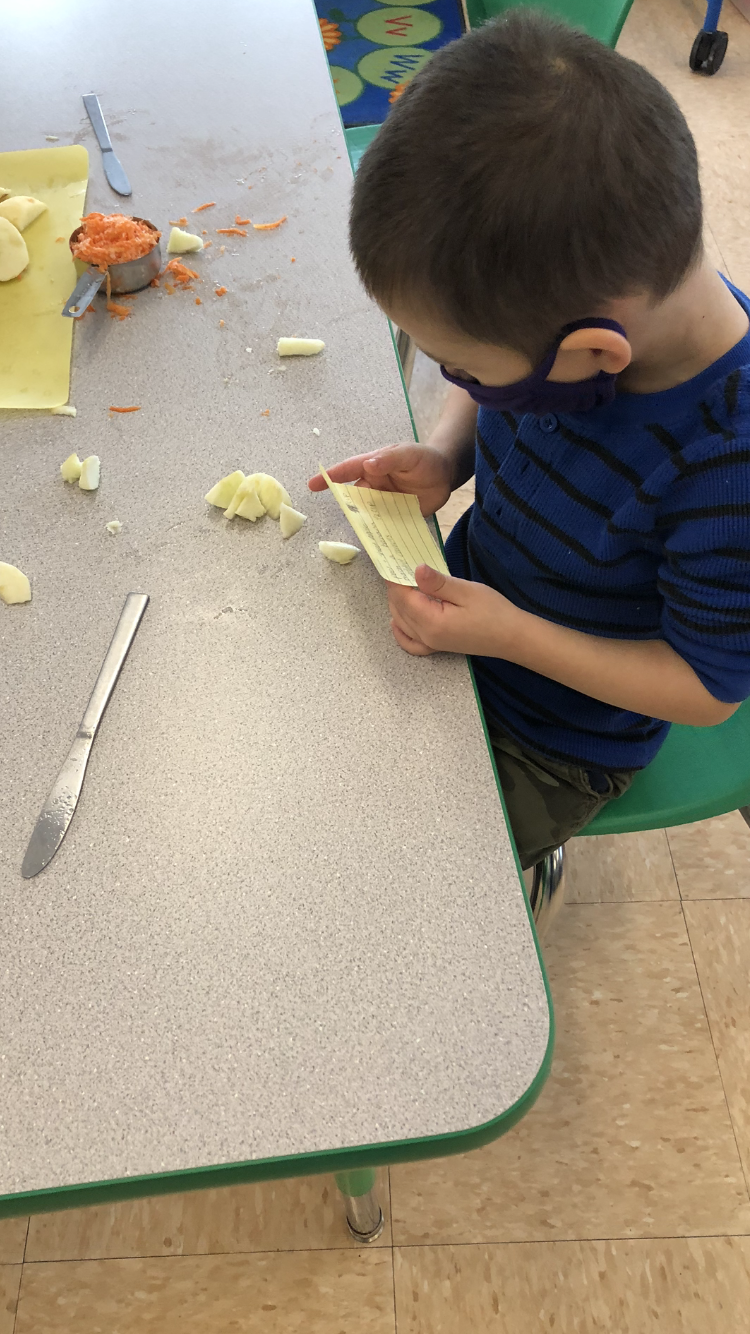

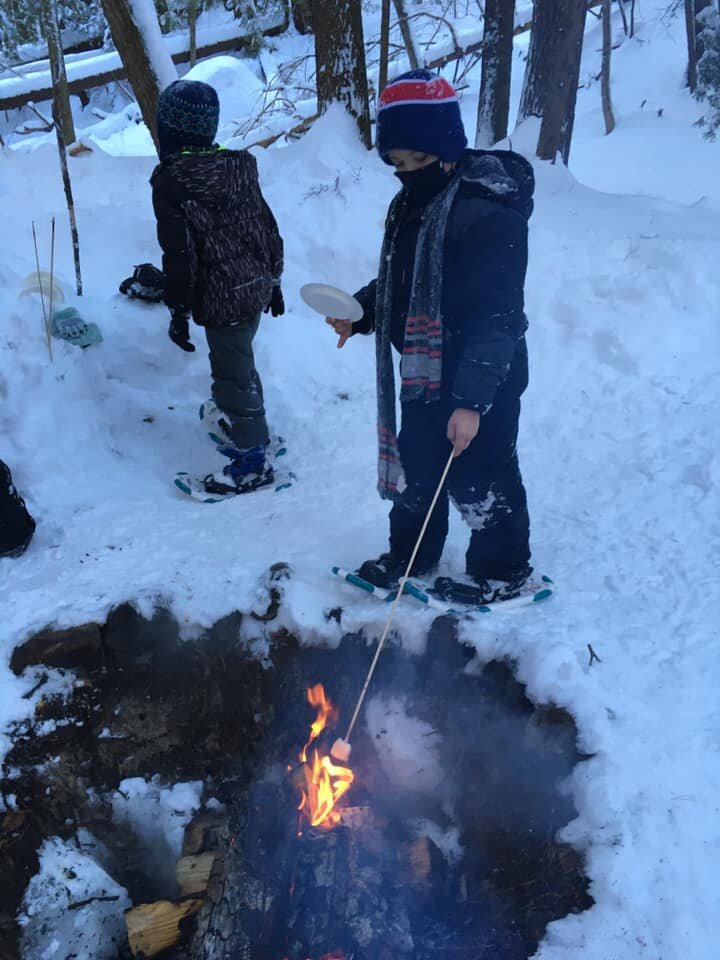

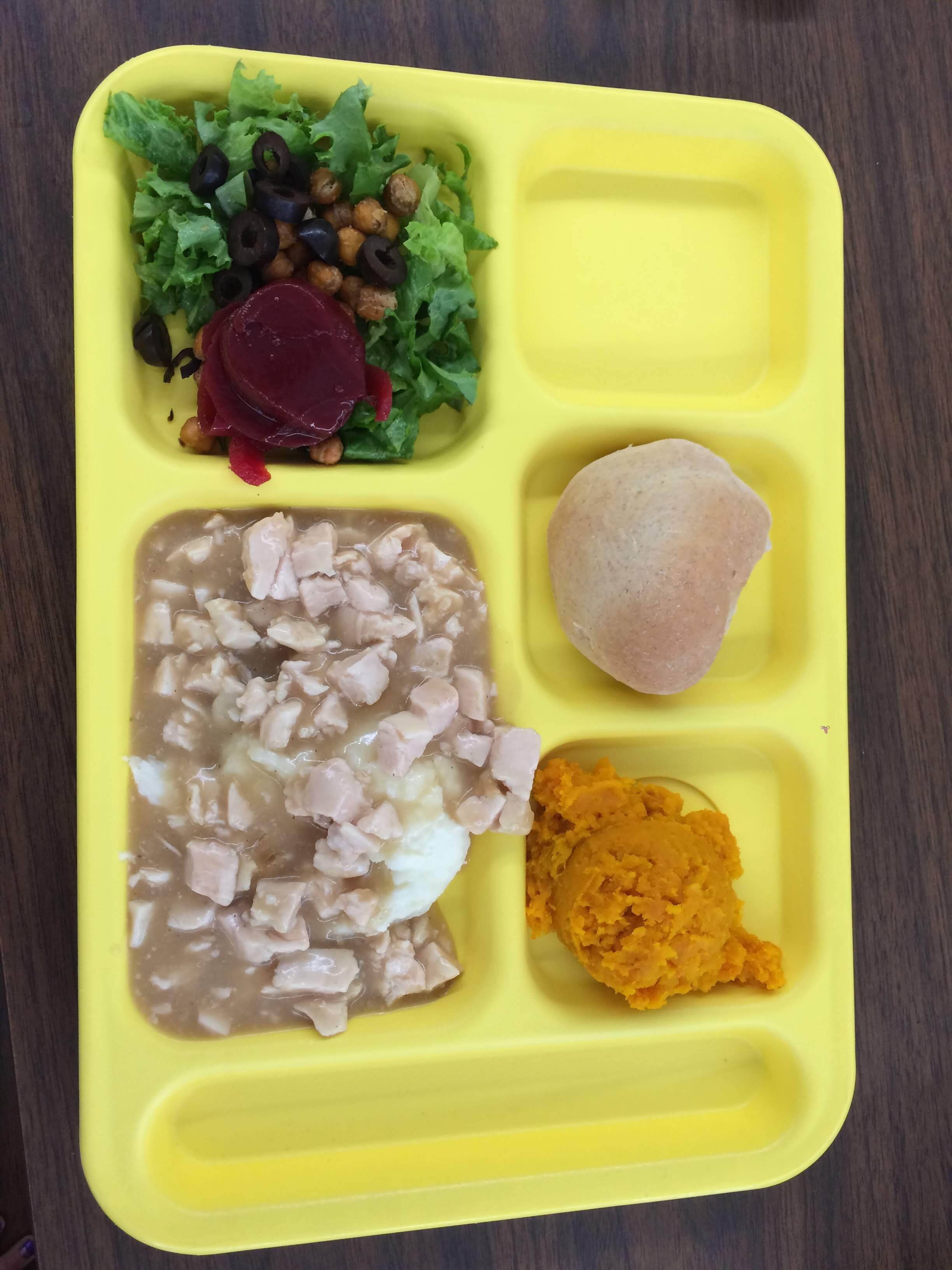

Produce that arrived weekly in the CSA share helped students make a connection to their school garden, where many of the same plants were growing. Tara regularly took students to the garden to harvest produce, and they combined their school garden-grown produce with produce from Full Plate Farm to cook some delicious recipes. The class cooked twice a week throughout the season, which was new and wonderful! Here are several of the most popular things they made:

Fresh vegetable spring rolls

Many soups, including stone soup and root vegetable soup

Sweet and salty radishes

Coleslaw

Jamie shared that often the students’ first response to the idea of new food was, “Yuck, I don’t like this!” but she discovered that when they cut the veggies into fun shapes or tried adding interesting flavors, for example, agave syrup to change the flavor of the radishes, students were pleasantly surprised to learn that in fact, they did like that food after all! For the more reluctant students, Tara introduced a five senses taste test, where the students closed their eyes and sometimes even plugged their noses when trying new food to focus on the texture of the food in their mouths.

The entire Oak Grove community benefitted from this in-depth study of local food and cooking by the Pre-K in several ways:

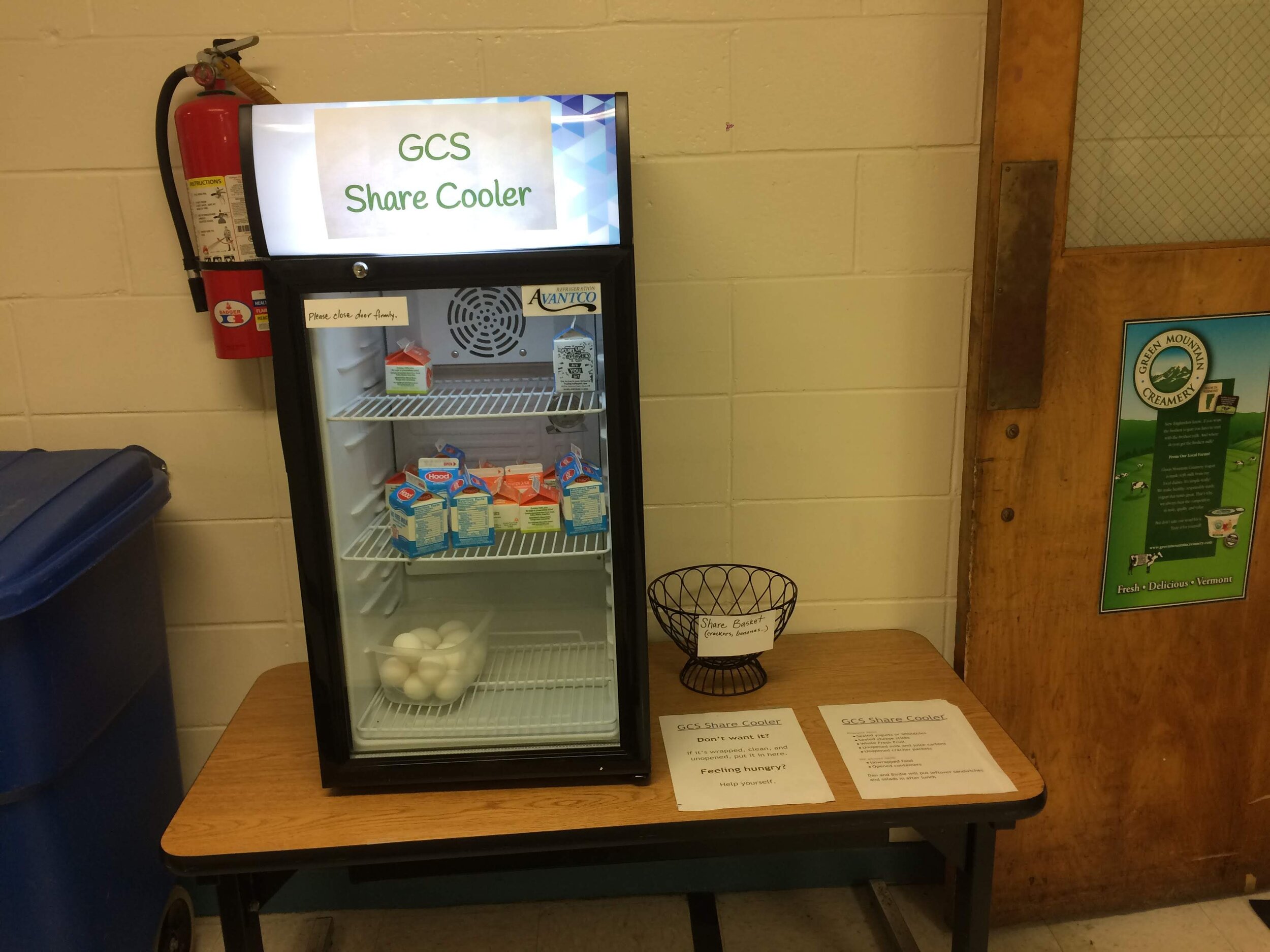

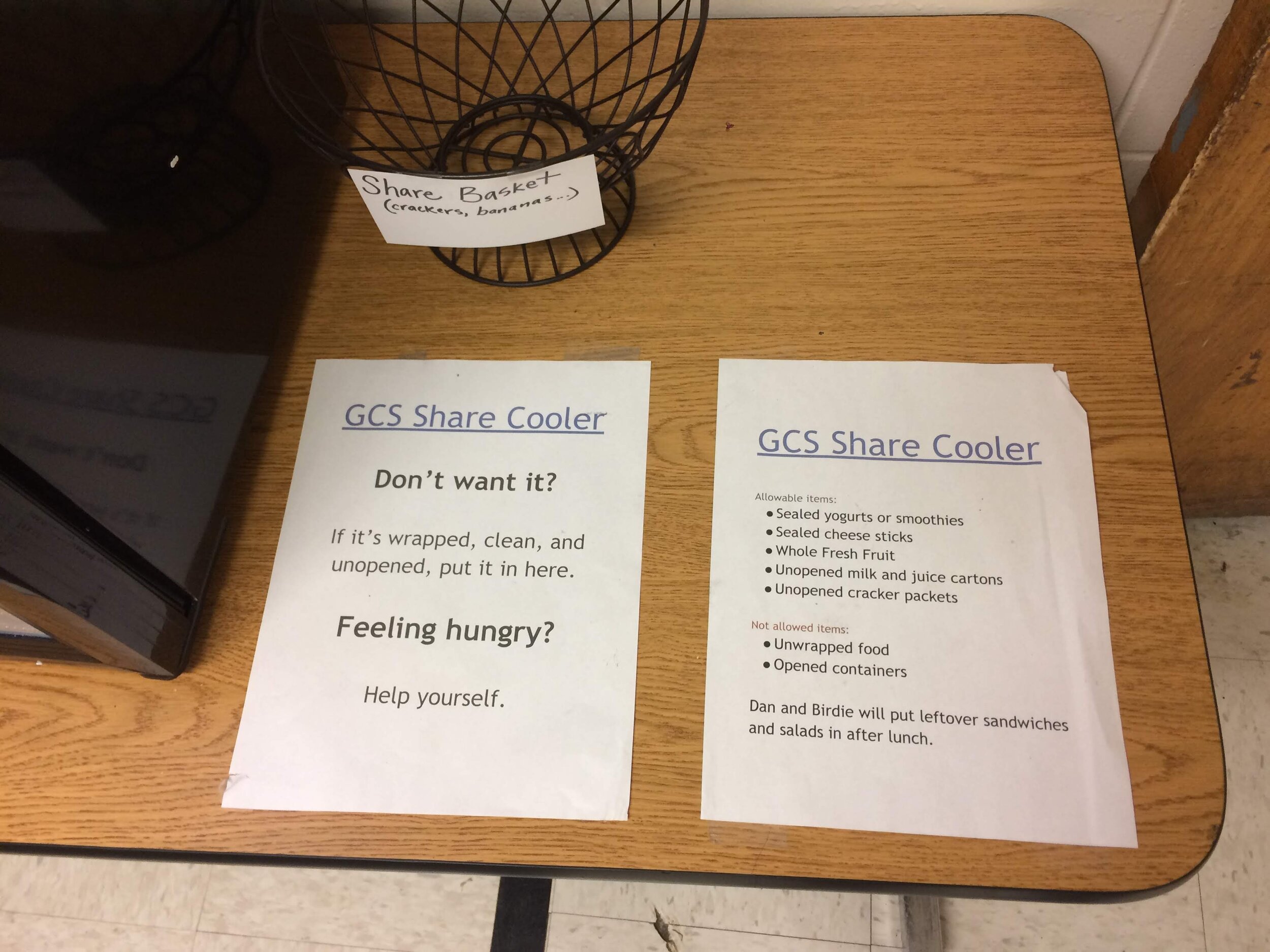

Food cooked by the Pre-K was often shared with school staff as a special meal. The staff got to enjoy several different soups and a root vegetable casserole prepared by the students and their teachers.

Bags of extra fresh produce were sent home regularly for students to share with their families. The produce came with a small sample of the meal that the students had made in school and the recipe, and families were encouraged to try the same recipe at home.

Extra produce was also shared with other classrooms in the school. For example, Erek Tuma’s 4th-grade class benefitted from pre-K’s abundance of kale for their kale Harvest of the Month taste test.

The classroom curriculum connections were particularly rich, linking cooking, gardening, and produce exploration with science and literacy. A visit from Ragan Anderson supported the program, nutrition educator from the Brattleboro Food Co-op, who came into the classroom, read stories with the students, and did a cooking project featuring butternut squash.

Jamie is already thinking about what she will do differently next season to improve the program. Some of her goals are:

Increase family feedback and family engagement. For example, send home every recipe with ingredients and invite families into school to participate in cooking and harvesting.

Build more community throughout the school. For example, have cooking buddies from other classes and cook for other classes.

Cook something once a week for staff.

Overall, this program was a huge success! As a result, the students are very excited about the school garden, and they look forward to cooking and gardening as a regular part of their weekly routine. Support from garden coordinator Tara Gordon was a key component to the success of this program, allowing students to spend time in the garden every week and engage in cooking activities throughout the whole season.